[dropcap]H[/dropcap]ealth is fundamental to individuals, families and the economy. As Julio Frenk wrote in Harvard International Review, “Good health reduces poverty, protects family assets, improves educational performance, increases labor productivity, enhances the investment climate and, through all of these things, stimulates economic growth.”[note]“Health and the Economy,” by Julio Frenk, Harvard International Review, June 14, 2014[/note]

One of the greatest challenges in health care today is improving access to care for rural, underserved urban and uninsured populations. Increasingly, health care systems are expected to deliver cost-effective quality care to more people. To meet this demand, health care systems often rely on digital health information and tools to enhance continuity of care and increase efficiency, timeliness and reach.[note]“Benefits of Telemedicine in Remote Communities and Use of Mobile and Wireless Platforms in Healthcare,” by Alexander Vo, G. Byron Brooks, Ralph Farr and Ben Raimer, University of Texas Medical Branch, 2011, https://telehealth.utmb.edu/presentations/benefits_of_telemedicine.pdf.[/note] One promising tool, telehealth, is an alternative-care model that can be deployed to address access-to-care issues for hard-to-reach populations, such as the residents of the Texas–Mexico border.

The Texas border region is a mix of urban and rural geographies and is one of four persistent poverty areas of the country.[note]United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. Persistent-poverty counties had poverty rates of at least 20 percent in each U.S. census, 1980, 1990 and 2000, and American Community Survey five-year estimates, 2007–11. Persistent poverty regions include: Central Appalachia, the Mississippi Delta, First Nation Communities (in New Mexico, Arizona and the Dakotas) and the Texas border region.[/note] Approximately 48 percent of people on the Texas–Mexico border live at or near the poverty line. An even larger percentage of residents in the periurban and rural colonias, 62 percent, live at or near poverty.[note]“Las Colonias in the 21st Century: Progress Along the Texas–Mexico Border,” by Jordana Barton, Emily Ryder Perlmeter, et al, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, 2015, www.texascolonias.org.[/note]

Research by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation found that a person’s zip code is more of a predictor of health outcomes and how long a person will live than their genetic code. Their study of life expectancy across the United States found that “geographic disparities in life expectancy in our nation . . . can be explained in large part by differences in race/ethnicity and socioeconomic factors such as income…” The study demonstrates that lower-income zip codes have significantly lower life expectancy than higher-income zip codes.[note]Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Commission to Build a Healthier America, www.rwjf.org/en/about-rwjf/newsroom/features-and-articles/Commission/resources/city-maps.html.[/note]

The Telehealth Tool

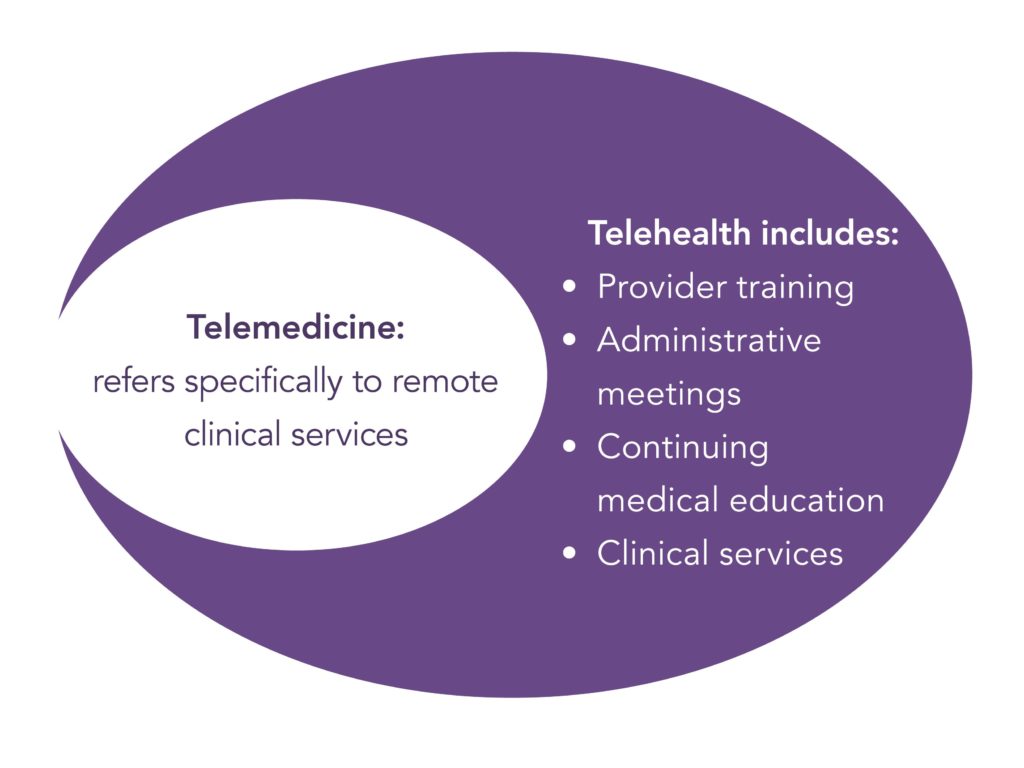

Telehealth is a useful model poised to make a significant impact on health challenges on the border.[note]This publication includes health data from seven counties along the Texas–Mexico Border: Cameron, Hidalgo, Starr, Webb, Maverick, El Paso and Willacy, Regional Health Plan for Region 5 Community Needs Assessment, Professional Research Consultants, Aug. 31, 2012. Also, “What’s Next? Practical Suggestions for Rural Communities Facing a Hospital Closure,” Texas A&M University Rural & Community Health Institute (RCHI), 2017, recommends telemedicine as one of the viable solutions to the health care access challenge in rural areas, www.rchitexas.org/news-release/rural-hospital.html.[/note] Telecommunication technologies are used in combination with other health services to deliver integrative health care to more patients regardless of geographic location. Greater efficiencies may be reached in telehealth by using more mid-level providers such as nurse practitioners and physician assistants for direct patient care in consultation with a physician through videoconferencing. Furthermore, primary care physicians can broaden their offerings by incorporating videoconferencing with specialists during appointments with patients.[note]“A Guide to Understanding Mental Health Systems and Services in Texas,” 3rd Edition, Hogg Foundation for Mental Health, 2016.[/note]

Some people who hear the terms “telehealth” or “telemedicine” express concerns that it means there is less in-person contact with a health care provider. Patients want a health care provider who is present, can interact personally with them and can perform a physical exam if necessary. However, telemedicine is not an either/or binary where the only options are to either meet with the doctor on a computer screen or meet in person at the doctor’s office. Most telemedicine programs, such as those highlighted in this publication, include a qualified health care provider who is physically present but also has the ability to videoconference with a supervising physician or specialist.

The University of Texas Medical Branch reported, “The integration of telehealth into the American health care system can offer unparalleled access to high-quality care to every citizen no matter where they live. The combination of sophisticated videoconferencing, electronic medical records, proven disease management protocols and telemonitoring can revolutionize medical care.”[note]“Benefits of Telemedicine in Remote Communities & Use of Mobile and Wireless Platforms in Healthcare,” by Alexander Vo, G. Byron Brooks, Ralph Farr and Ben Raimer, University of Texas Medical Branch, 2011, https://telehealth.utmb.edu/presentations/Benefits_Of_Telemedicine.pdf.[/note] Telehealth has proven to be effective for improving access to specialists, increasing patient satisfaction with care, improving clinical outcomes, reducing emergency room utilization and increasing cost savings.[note]“The Telehealth Promise: Better Health Care and Cost Savings for the 21st Century,” by Alexander H. Vo, AT&T Center for Telehealth Research and Policy, Electronic Health Network, University of Texas Medical Branch, May 2008, https://telehealth.utmb.edu/presentations/The%20Telehealth%20Promise-Better%20Health%20Care%20and%20Cost%20Savings%20for%20the%2021st%20Century.pdf.[/note]

Thus, telehealth is increasingly seen as an effective means for serving patients who are limited by poverty, geography, lack of insurance and debilitating health challenges. Many of these challenges are evident in the health disparities found on the Texas-Mexico border.

Health Disparities on the Border

The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston School of Public Health defines health disparity as “diseases, disorders and conditions that are unique to, more serious, or more prevalent in subpopulations in socioeconomically disadvantaged and medically underserved, rural and urban communities.”[note]Lisa Mitchell-Bennett, “Evidence-Based Strategies to Change Behavior and Promote Health” (presentation delivered at the Rio Grande Valley Regional Convening at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, Sept. 14, 2017).[/note] The Texas–Mexico border has a high prevalence of diabetes and related conditions such as obesity, tuberculosis, depression and anxiety. The region also experiences disparities related to access to care, such as a lack of access to health care facilities, a high uninsured population and a shortage of health care providers.

Prevalent Diseases. The general population of the border region is about 90 percent Hispanic, and the periurban and rural colonias are 96 percent Hispanic.[note]“Las Colonias in the 21st Century: Progress Along the Texas–Mexico Border,” by Jordana Barton, Emily Ryder Perlmeter, et al, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, 2015, www.texascolonias.org.[/note] The Cameron County Hispanic Cohort study, which is considered to be the most comprehensive study of diabetes on the Texas-Mexico border to date, evaluated a group of over 2,000 randomly selected Mexican American adults and found that 30.7 percent had diabetes.[note]Joseph B. McCormick, M.D., “Population Health in Cameron County: An Update from the Cameron County Hispanic Cohort Study” (presentation delivered at the Rio Grande Valley Regional Convening at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, Sept. 14, 2017).[/note] In contrast, the rate of diabetes nationally is 11.3 percent. For Mexican–Americans across the U.S., the diabetes rate is 13.4 percent—substantially less than rates found in the Cameron County Hispanic Cohort study.[note]Regional Health Plan for Region 5 Community Needs Assessment, Professional Research Consultants, Aug. 31, 2012.[/note]

The Cameron County Hispanic Cohort study noted that nearly half of those with diabetes are undiagnosed, and over 55 percent are untreated. Untreated diabetes is common among patients admitted to the hospital for serious health issues such as cardiovascular disease and sepsis. In addition, the Rio Grande Valley—the four-county region along the southern border which includes Cameron, Hidalgo, Willacy and Starr counties—has the highest rates of diabetes-related amputations. Moreover, poor mental health has been linked to diabetes, obesity and limited physical activity.[note]Lisa Mitchell-Bennett, “Evidence-Based Strategies to Change Behavior and Promote Health” (presentation delivered at the Rio Grande Valley Regional Convening at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, Sept. 14, 2017).[/note] The Regional Health Plan for Region 5, which includes the four Rio Grande Valley counties, reported 28.6 percent of adults experience a measurable level of depression, while 30 percent of adults have measurable levels of anxiety, rates that are well above what we see in the broader population.[note]Regional Health Plan for Region 5 Community Needs Assessment, Professional Research Consultants, Aug. 31, 2012.[/note]

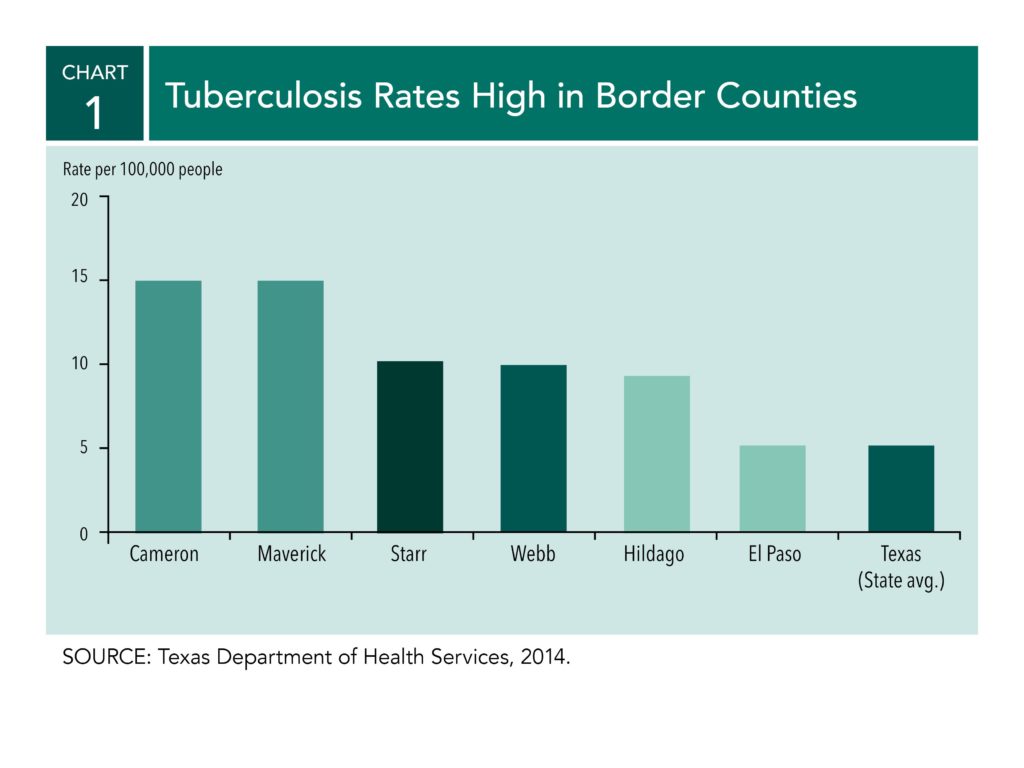

Among the Cameron County Hispanic Cohort, nearly 49 percent of the study participants were obese. Overall, approximately 90 percent were overweight, obese or extremely obese. This high instance of unhealthy body mass index translates to a population at high risk of developing diabetes and associated illnesses and infectious diseases. For example, people with diabetes have an increased susceptibility to infectious diseases such as tuberculosis. The border region continues to have the highest rates of tuberculosis in the nation with Maverick and Cameron counties exceeding 15 cases per 100,000 people. Tuberculosis in Texas averages 4.7 cases per 100,000 people.[note]Texas Department of State Health Services, 2014, www.dshs.texas.gov/.[/note]

Limited Access to Health Care. The Dallas Fed’s “Las Colonias in the 21st Century” report documented the issue of limited access to health care in the border region. The report cites county-level data; thus, it is relevant beyond the colonias to the wider border region. Three key challenges were noted.

First, low-income border residents rely primarily on community clinics in or near urban areas for medical care. The clinics are often overbooked and do not have many choices for referring patients to public hospitals for acute care. And, those residents who live in deep rural areas do not have health care facilities nearby; thus, they are required to travel long distances for care.[note]“Las Colonias in the 21st Century: Progress Along the Texas–Mexico Border,” by Jordana Barton, Emily Ryder Perlmeter, et al, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, 2015, www.texascolonias.org.[/note]

Second, the region has a high uninsured population. Preventive health care often depends on patients having insurance. Between 30 and 40 percent of adults under age 65 in the border region are uninsured, compared with 26.8 percent in Texas. Uninsured residents may delay receiving care until their conditions are more acute, often requiring costly emergency room visits.[note]Texas Department of State Health Services, 2014, www.dshs.texas.gov/.[/note] [note]A discussion of the impact of the uninsured population relying on emergency room visits for primary care can be found in “Las Colonias in the 21st Century: Progress Along the Texas–Mexico Border,” by Jordana Barton, Emily Ryder Perlmeter, et al, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, 2015, www.texascolonias.org.[/note]

Third, there is a shortage of health care providers. The health care challenge is magnified in South Texas by the lower ratio of health care professionals in comparison with the rest of the state. These include physicians, dentists, physician assistants and nurse practitioners.[note]“Las Colonias in the 21st Century: Progress Along the Texas–Mexico Border,” by Jordana Barton, Emily Ryder Perlmeter, et al, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, 2015, www.texascolonias.org.[/note] For example, the entire border region is designated a mental health professional shortage area.[note]“A Guide to Understanding Mental Health Systems and Services in Texas,” 3rd Edition, Hogg Foundation for Mental Health, 2016. [/note] With an increasing need for support and services for mental health issues associated with prevalent diseases along the southern border, the shortage of professionals to provide required care creates a particular challenge for the region.

Digital Divide Limits Use of Telehealth

The Texas–Mexico border region has some of the greatest health disparities and one of the greatest digital divides in the country.[note]“Closing the Digital Divide: A Framework for Meeting CRA Obligations,” by Jordana Barton, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, 2016, www.dallasfed.org/cd/pubs/digitaldivide.aspx.[/note] The digital divide is the gap between people who have access to broadband services and know how to use the internet and those who do not have such access or knowledge.[note]The Next Generation Network Connectivity Handbook: A Guide for Community Leaders Seeking Affordable, Abundant Bandwidth, by Blair Levin and Denise Linn, Benton Foundation, vol.1.0, July 2015, http://www.gig-u.org/cms/assets/uploads/2015/07/Val-NexGen_design_7.9_v2.pdf.[/note] Broadband is a high-speed internet service that is always on and has sufficient speeds for uninterrupted transmission of data. The Federal Communication Commission’s (FCC) defines broadband as a download speed of 25 Mbps (megabits per second) and 3 Mbps for uploads.[note]“2016 Broadband Progress Report,” Federal Communications Commission, Jan. 29, 2016, www.fcc.gov/reports-research/reports/broadband-progress-reports/2016-broadband-progress-report.[/note] Limited broadband infrastructure prevents the region from using telehealth widely to improve health outcomes. While there is an opportunity with technological advancements in health care to reach underserved areas more effectively, if the digital divide is not bridged, the benefits of innovation will bypass those areas because of an outdated or nonexistent digital infrastructure. Both medical innovation and digital infrastructure need to work in tandem. According to Pete Otholt, senior IT&S manager for Methodist Healthcare Ministries of South Texas Inc. and member of the Digital Inclusion Alliance San Antonio, “While telehealth offers a proven solution to the gap in access to care, it is necessary to recognize that limited broadband infrastructure and access in underserved and rural areas limits the application of telehealth for regions most in need.”[note]Pete Otholt (senior IT&S manager for Methodist Healthcare Ministries of South Texas Inc.), in discussion with the author, Sept. 20, 2017.[/note]

Moreover, as technology advances, the digital divide could also constrain the economic productivity of the health care industry. . This is especially significant since in the last quarter of 2017, “for the first time in history, health care . . . surpassed manufacturing and retail . . . to become the largest source of jobs in the U.S.”[note]“Health Care Just Became the U.S.’s Largest Employer,” by Derek Thompson, The Atlantic, Jan. 9, 2018.[/note] In the state of Texas, health services is one of the top three fastest-growing industry clusters.[note]“At the Heart of Texas: Cities’ Industry Clusters Drive Growth,” by Pia Orrenius, Laila Assanie, et al, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, 2016, www.dallasfed.org/research/heart. [/note] Indeed, in the El Paso metro area, the health services industry cluster ranks as the second-fastest in employment growth. In the McAllen–Edinburg–Mission metro area, on the lower Rio Grande Valley border, health services ranks among the top three industry clusters.[note]“At the Heart of Texas: Cities’ Industry Clusters Drive Growth,” by Pia Orrenius, Laila Assanie, et al, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, 2016, www.dallasfed.org/research/heart.[/note] Although health services is a large and growing industry, access to care challenges noted in the previous section continue to inhibit improved health outcomes for residents. The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley School of Medicine, which admitted its first class in 2016, has been heralded as a beacon of hope for the future of health care in South Texas. Francisco Fernandez, M.D., a faculty member at the school, noted, “In order to mobilize our students and faculty to address our community’s serious health disparities, such as diabetes, we will need broadband infrastructure and connectivity that will allow service in remote areas through telehealth.”[note]Francisco Fernandez, M.D. (professor, Department of Psychiatry, Neurology and Neurosciences, University of Texas Rio Grande Valley School of Medicine), in discussion with the author, May 22, 2017.[/note]

Harnessing the promise of telehealth requires communities to first determine broadband availability—recognizing that sufficient and reliable broadband speeds are required to accommodate the use of secure videoconferencing and transmission of high-definition images commonly used in telehealth. It is also important for health care institutions to partner with local governments as they develop their digital inclusion plans to ensure broadband capacity and speed will support telehealth.[note]Closing the Digital Divide: A Framework for Meeting CRA Obligations,” by Jordana Barton, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, 2016, www.dallasfed.org/cd/pubs/digitaldivide.aspx.[/note] [note]“What Speed Do you Need” Infographic, National Telecommunications & Information Administration, Broadband USA, www.ntia.doc.gov[/note] A comprehensive guide to closing the digital divide is provided in “Closing the Digital Divide: A Framework for Meeting CRA Obligations.”[note]“Closing the Digital Divide: A Framework for Meeting CRA Obligations,” by Jordana Barton, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, 2016, www.dallasfed.org/cd/pubs/digitaldivide.aspx.[/note] The publication also describes an effort underway to expand broadband access and digital inclusion on the border in the section, Digital Opportunity for the Rio Grande Valley, South Texas. One of the key goals of the project is to create a robust fiber-optic network that will enable the use of telehealth throughout the border region.

Another important reason to close the digital divide is to provide the capacity to use telehealth for emergency response. In 2017, telemedicine was deployed to address health needs during major hurricanes.[note]“In Mega-shelter for Harvey Evacuees, Telemedicine Plans to Help Doctors Keep Up” by Leah Samuel, STAT (Boston Globe Media), Aug. 31, 2017, www.statnews.com/2017/08/31/harvey-shelter-telemedicine/.[/note] [note] “New York–Presbyterian Specialists Use Telemedicine to Treat Stranded Puerto Ricans” by Bill Siwicki, Healthcare IT News, Nov. 9, 2017, www.healthcareitnews.com/news/newyork-presbyterian-specialists-use-telemedicine-treat-stranded-puerto-ricans.[/note]

Telehealth Initiatives in Texas and Louisiana

The digital divide presents a barrier to the use of telehealth in the border region. However, four accounts from various locations in the Eleventh Federal Reserve District demonstrate the opportunity for telehealth to address the specific health challenges that exist along the border. The initiatives described below are from both urban and rural geographies and represent efforts to use telehealth to reach the underserved.

Bringing Telehealth to the Colonias

The colonias, the lowest-income communities of the border, have been a public health focus of government agencies, community advocates, elected officials and residents for over three decades due to the lack of basic infrastructure and substandard housing—and the impact of those conditions on health outcomes. An organization serving the colonias, La Union del Pueblo Entero (LUPE), is partnering with a regional hospital system to use telehealth to improve access to care. “We are the connectors,” explained Tania Chavez, systems strategist and development manager for LUPE. “We’re the middlemen between the community and the health system,” she said.

LUPE is a community-based organization located in San Juan, Texas, in Hidalgo County. Its focus is to build stronger, healthier communities where residents use the power of civic engagement for social change. LUPE’s grassroots connection with the communities it serves has helped create access to valuable programs and services that have improved the quality of life in the border region. Health on Wheels (HoW) is a telehealth program administered by LUPE in partnership with Methodist Healthcare Ministries of South Texas Inc., the Valley Baptist Legacy Foundation and Doctors Hospital at Renaissance to broaden access to health care in low-resource communities.

The HoW program offers a holistic approach to health through its outreach efforts. These include:

- Mobile health clinics

- Community health workshops focused on preventive care led by University of Texas Rio Grande Valley medical school residents and other health advocates

- Leadership training for certified promotoras (community health educators) through the Texas A&M Colonias Program.[note]The Texas Department of State Health Services defines promotoras as community health care workers who inform residents about health-related issues and who teach families health care literacy, Texas Community Health Worker Program, March 2014, www.dshs.texas.gov/mch/chw/Community-Health-Workers_Program.aspx.[/note]

The mobile clinics operate out of a motor home retrofitted with high-definition videoconferencing equipment and state-of-the-art medical devices to offer general medical services, vision and specialty care. Services include low-cost vision exams and eyeglasses, diabetes prevention and care, women’s health and mental health care.

Certified promotoras are a vital asset to the program as they successfully engage with the community to schedule appointments for the mobile unit, encourage attendance at health workshops and recruit future promotoras. Prior to partnering with LUPE, Doctors Hospital at Renaissance was unable to attract patients to its mobile clinic. However, once the hospital partnered with LUPE, its mobile unit became an effective way for border residents to receive health care.

The HoW program plays a critical role in the community by identifying unmet health needs and serving the uninsured. Indeed, 91 percent of patients served through the program lack any form of health insurance, and the mobile clinic is the only place medical care is received by 13 percent of its patients. The mobile clinics also serve as an important entry point into the health system—34 percent of mobile clinic patients have been referred to other community clinics for follow-up care.[note]Tania Chavez, “La Union del Pueblo Entero Health on Wheels” (presentation delivered at the Rio Grande Valley Regional Convening at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, Sept. 14, 2017).[/note]

Transforming Diabetes Care

Methodist Healthcare Ministries of South Texas Inc. serves low-income patients who typically do not have health insurance, often struggle to find reliable transportation and sometimes live in rural areas with limited access to basic health care and specialists. Pete Otholt, with Methodist Healthcare Ministries of South Texas Inc., emphasizes “the importance of telemedicine as a means of providing integrated, responsive and cost-effective health care services to underserved populations. For diabetes patients, real-time support is especially important as many factors contribute to managing the disease.”[note]“Interrupting the Cycle of Diabetes,” https://medium.com/@ibmcognitivebusiness/interrupting-the-cycle-of-diabetes-600380ddfd02.[/note]

As part of an initiative to provide integrated health care in real time, Methodist Healthcare Ministries of South Texas Inc. and Medtronic developed the Turning Point pilot program for diabetic patients with uncontrolled HbA1c (A1C) levels—a measure of a person’s average level of blood glucose, or blood sugar, over three months. The six-month pilot program used a smartphone digital app to monitor diabetes progress and offer real-time support, without which, many patients fail to manage the disease effectively. For example, Philip Fisher, a San Antonio chef who plans and prepares meals for Outcry in the Barrio Ministry, was diagnosed with diabetes in 2014. Like many diabetes patients, Fisher was overwhelmed with managing the disease on his own, so he ignored it. When his doctor suggested he participate in the Turning Point program, Fisher had an A1C level of 10.9 percent. His A1C level was well above the 7 percent target A1C for people with diabetes set by the American Diabetes Association.[note]American Diabetes Association, www.diabetes.org.[/note]

The Medtronic app helped Fisher keep track of his blood glucose levels, blood pressure, sleep patterns and weight. As with each patient in the program, he was assigned to a Medtronic care coordinator who: 1) completed his enrollment; 2) helped with equipment troubleshooting; 3) maintained open communication through in-person or phone check-ins; 4) tracked Fisher’s progress through the app; 5) timely communicated health information to his physician to avoid further health complications; and 6) offered diet counseling. Fisher experienced significant improvement. He brought his AIC level down 5 points to 5.9 percent, which is below the diabetic range. These results inspired Fisher to begin preparing healthier meals for the men he serves in his ministry.[note]“A Chef Takes a Fresh Approach to Diabetes,” https://medium.com/cognitivebusiness/a-chef-takes-a-fresh-approach-to-diabetes-4235fad1f222.[/note]

Overall, the program was successful at improving patients’ A1C numbers by an average of 2.0 points. Fisher and other patients lost weight, benefited from increased energy and became role models for others in their families and community. Positive health outcomes and patient satisfaction led to continuation of the program.[note]“A Chef Takes a Fresh Approach to Diabetes,” https://medium.com/cognitivebusiness/a-chef-takes-a-fresh-approach-to-diabetes-4235fad1f222.[/note]

Improving Health Care Access for Rural Veterans

The Rural Veterans Coordination Pilot Program (RVCP), operated by Volunteers of America North Louisiana in partnership with the Overton Brooks VA Medical Center in Shreveport, Louisiana, was originally a two-year program extended to three years that provided psychiatric services to veterans in underserved areas by using telemedicine to complement services offered at the VA medical center. The $2 million project, sponsored by the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), outfitted a cargo van that served as a state-of-the art mobile clinic using satellite technology. At the mobile clinic, telemedicine appointments were facilitated by an on-site nurse or social worker and were videoconferenced from Overton Brooks VA Medical Center.

Bryan Byrd, executive vice president of innovation and new business development for Volunteers of America North Louisiana asserts, “The program improved the quality of life for veterans and their families. The RVCP has demonstrated savings of thousands of miles not traveled. The average mileage traveled by rural veterans to the Overton Brooks VA Medical Center is 145 miles per visit, with the program’s average annual travel savings exceeding $1,800 per veteran.”[note]Bryan Byrd (executive vice president of innovation and new business development for Volunteers of America North Louisiana), in discussion with the author, Oct. 9, 2017.[/note] While the individual cost savings to veterans is significant, the program also improved outcomes for the VA medical center with a 59 percent reduction in in-bed days of care and a 35 percent reduction in hospital readmissions. Furthermore, the program reduced the number of missed appointments, improved veteran access to preventive care and reduced higher-cost emergency room use. The nonprofit applied for continued support from the VA, and it is looking to diversify funding by applying for grants from other sources. This will enable the organization to expand telemedicine services from a focus on psychiatry to include additional services such as dermatology, diabetes management, long-term care and post-acute care.[note]Bryan Byrd (executive vice president of innovation and new business development for Volunteers of America North Louisiana), in discussion with the author, Oct. 9, 2017.[/note]

In an article detailing the work of the RVCP, Jen Fifield of the Pew Charitable Trusts notes, “While long drives and limited access to health care are familiar burdens for many rural residents, the problem is particularly acute for veterans in those areas. They are far older than other rural residents and far more likely to be disabled, meaning more of them are in need of medical care. And, there are a lot of them—one in four veterans lives in rural areas, as compared to one in five adults in the general population, according to 2015 census data.”[note]“For Rural Veterans, New Approaches to Health Care,” by Jen Fifield, the Pew Charitable Trusts, Aug. 3, 2017, www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2017/08/03/for-rural-veterans-new-approaches-to-health-care.[/note]

Diverting Unnecessary High-Cost Emergency Room Visits

In 2014, the Houston Fire Department began a partnership with the Houston Department of Health and Human Services along with 13 other community organizations to introduce the Emergency Telehealth and Navigation Project (ETHAN) to ease emergency department overcrowding and overuse. The goal of ETHAN is to reduce the stress on emergency response resources by diverting nonemergency patients to other less cost-intensive resources.[note]“Healthcare Council Features Project ETHAN (Emergency TeleHealth and Navigation),” Greater Houston Partnership, 2015, www.houston.org/assets/pdf/news/July-Healthcare-Council-Recap.pdf.[/note]

Paramedics connect patients with minor injuries or illnesses by video to an emergency physician using a tablet device powered by wireless technology. The physician determines whether the patient needs to go to the emergency room, what mode of transportation is best suited to the patient’s level of acuity or whether the patient should see a primary care doctor instead. In cases where an emergency room visit is not necessary, appointment arrangements and transportation are coordinated for the patient. In cases where ETHAN was used, 80 percent of unnecessary ambulance and emergency room visits were averted.[note]“Project ETHAN Telehealth Program Cuts Number of Emergency Department Transports in Houston,” by Karen Appold, ACEPNow, July 15, 2015, www.acepnow.com/article/project-ethan-telehealth-program-cuts-number-of-emergency-department-transports-in-houston/.[/note]

Conclusion

This publication documents the positive role telehealth can play in serving populations most in need of quality and appropriate health care. LUPE’s HoW program, mentioned earlier, illustrates an important lesson: Technological innovations can be coupled with innovative community development approaches to reach low- and moderate-income populations. Furthermore, to unleash the full potential of telehealth, underserved urban and rural communities will need to address the digital divide.

The significant role of broadband access to the provision of health services has led Mignon Clyburn, a commissioner of the Federal Communications Commission, to call broadband access one of the social determinants of health. Clyburn recognizes that broadband is critically important to health outcomes and must be addressed along with the other social determinants of health: physical environment, socioeconomic factors, health care access and health behaviors.[note]Remarks of Commissioner Mignon L. Clyburn of the Federal Communications Commission at the Launch of the Mapping Broadband Health in America Platform, Microsoft Innovation and Policy Center, Aug. 2, 2016, https://apps.fcc.gov/edocs_public/attachmatch/DOC-340590A1.pdf.[/note] While the digital divide can be a barrier to positive health outcomes, the reverse is also true. Closing the gap can transform the provision of health care on the border and achieve positive health outcomes for its residents.